Where did Edmonton get its name?

The origin of Edmonton’s name isn’t glamorous, but it dates back almost a millennium

The origin of Edmonton’s name isn’t glamorous, but it dates back almost a millennium. Our city was named after Edmonton, England, an area in the borough or district of Enfield, which is part of the Greater London area.

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) brought the name across the Atlantic in the eighteenth century. In 1795, HBC built the first Fort Edmonton on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River near present-day Fort Saskatchewan. They named it Edmonton House or Fort Edmonton. This was the first fort to bear that name. Five different Fort Edmontons were built over the next 50 years as previous iterations were destroyed by floods or abandoned due to lack of customers. The fifth and final fort was constructed in 1840 on the site of the current Alberta Legislature grounds, where a lawn bowling green now stands.

View of the exterior of the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Edmonton, in front of the new Legislative Building for the Province of Alberta, ca. 1915

The reason for naming the fort “Edmonton” is murky and not recorded in the journals of the HBC, according to Gerhard Ens, a professor of history and classics at the University of Alberta. Ens’s research interests include 19th and 20th century Métis society and politics, the fur trade, the missionary west and ethnic settlement. He is currently working on a multivolume scholarly edition of the Edmonton House fur trade journals, of which the first two volumes (1806-21; 1821-26) have already been published.

“In all likelihood, William Tomison, who established the post for the HBC in 1795, named the post Edmonton House after Edmonton, Middlesex, which was the home of Sir James Winter Lake, the deputy governor of the HBC,” Ens writes in an email.

Ens said Lake was a member of the company’s London Committee from 1762 to 1781, served as deputy governor from 1782 to 1799, and was governor from 1799 to 1807. The Middlesex Edmonton was located about 13 km north of the HBC’s head office on Fenchurch Street, which is now a part of Greater London.

Not much else is known about the process behind why Lake’s birthplace was chosen as the new fort’s name. Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie (University of Alberta Press, 2004) records the history and origins of Edmonton’s various place names. Under the entry for Edmonton, the book simply reads: “Fort Edmonton was named for the English birthplace of Sir James Winter Lake. He was present at the meeting of the governors of the HBC when it was decided to establish a fort on the North Saskatchewan River.”

In addition to Lake, some sources also list John Peter Pruden, an apprentice with the HBC who was also from Edmonton, Middlesex, as the person responsible for supplying the fort’s name. Ens does not think this claim is very credible, however. “It is unlikely that an apprentice had any role in the naming of the post,” Ens writes.

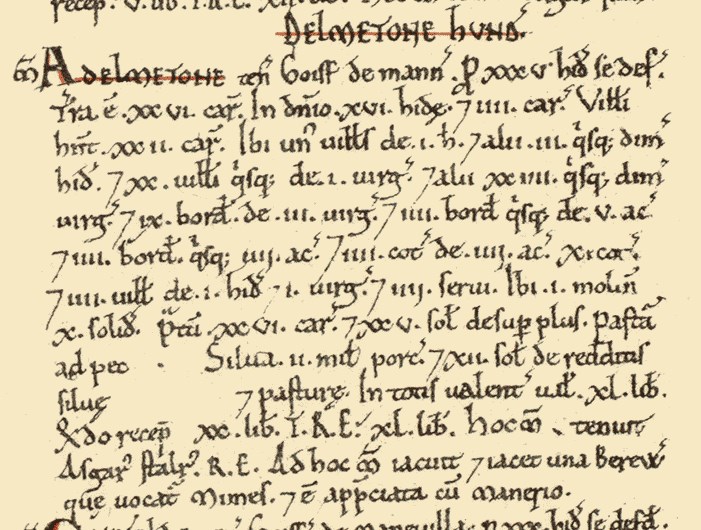

Edmonton, photo by Open Domesday

The first reference to “Edmonton” as a place name appears in the Domesday Book (pronounced “Doomsday”), a manuscript published in 1086 that recorded the property values of English landowners and the taxes they owed to King Richard III. The Domesday Book contains a reference to Adelmetone, which means “farmstead of a man called Ēadhelm” according to A Dictionary of British Place Names.

Naming Edmonton elaborates further: “The name “Edmonton” is derived from the Anglo-Saxon Christian name Eadhelm and ‘tun’ or ‘ton,’ which means a ‘field’ or ‘enclosure.’ ”

So, “Edmonton” refers to a person named Eadhelm who owned a particular plot of land in England at the time a royal census was taken. Over time, the name evolved into the modern spelling and the area grew into the town that was absorbed into London.

Of course, Edmonton is only one name for this area, which has been inhabited by people for at least 8,000 years. Most of the Indigenous names were replaced by names chosen by white settlers, including Edmonton itself.

Beaver Hills House Park, 105 Street & Jasper Avenue, photo by Mack Male

Probably the best-known Indigenous name for this area is the Cree name, amiskwacîwâskahikan, which has been translated as Beaver Hills House. This area was known as the Beaver Hills in several Indigenous languages, according to local history book Edmonton In Our Own Words (University of Alberta Press, 2004). The book also records other Indigenous names for this area: “The Nakoda Sioux, known then as the Assiniboines, said ti oda, meaning Many Houses. The Blackfoot called the trade forts omahkoyis, which means Big Lodge.”

The book also notes a couple other names for this area: Forts des Prairies, used by French-speaking Métis and French-Canadian voyageurs – this name was used for other posts on the North Saskatchewan River as well – and Fort Sans Pareil (“Unmatched Fort”), used by fur traders for a short time.

Rossdale, photo by Kurt Bauschardt

Another name for the specific area now called Rossdale, where the old power plant is located, is pehonan. This is a Cree word meaning waiting place or gathering place. Rossdale has come under scrutiny in recent years due to various development proposals and competing priorities for the future use and vision of this area.

Names are powerful. Most of Edmonton’s place names create a “veneer of colonialism” that colours our view of this place, says Matt Dance, an urban geographer and open data advocate. Dance became interested in Edmonton’s place names after coming across Naming Edmonton. He’s currently digitizing the book on the Naming Edmonton website, in the hopes of quantifying his hypothesis that the vast majority of Edmonton’s place names are British and/or male. Dance has also created a dataset of Edmonton’s Indigenous place names, available through the City of Edmonton’s open data portal.

Dance says names have a strong influence over the way we feel about a place. Edmonton’s largely white and British names may be comfortable for people who share that background, he says, but what about those who don’t?

“I think if we were able to get at the First Nations names for the specific places in Edmonton – and I mean the culturally appropriate geographic names of places – then, No. 1, we would have a very different relationship with the First Nations people who currently live here,” he says. “We’d have a very different relationship with the past. And we would have, I think, a much richer understanding of what this place is.”

But it’s not as easy as simply replacing one set of names with another. Over time, names also grow and evolve. “Edmonton” used to simply refer to a British town, but the growth of our city has established it as a name unto itself. This was demonstrated by the work of Erik Backstrom, a senior planner with the City of Edmonton, who found 145 streets around the world that were named “Edmonton.” Of these, the majority are named after Edmonton, Alberta, instead of the London neighbourhood, including 15 of the 22 Edmonton-named streets in the UK itself.

Edmonton Green Station Roundel, photo by London Moving

“The name ‘Edmonton’ has taken on its own life – it’s established as this city,” says Cory Sousa, principal planner with the City of Edmonton, who works with the Naming Committee. He notes that Edmonton has had a few big name changes over the years, such as renaming Calgary Trail northbound to Gateway Boulevard. That application was a great example of what it takes to successfully rename something in the city, he explains.

“Those most affected by it should really be coming forward,” he says. “It would have to be driven by the community, it would require a lot of community support, and then the final decision would be made by City Council.”

That names take on their own life, no matter their origin, is part of why people get so emotionally invested in discussions about them. Edmonton experienced this in 2017 during the debate around the legacy of Frank Oliver and the proposal to change the name of the Oliver neighbourhood. The debate demonstrated an appetite to examine and address some of Edmonton’s place names that we’ve previously taken for granted. And in doing so, we begin to face things that are uncomfortable to many: the ways in which colonialism has shaped how we think of and feel in this place, and how we might start to change that.

So far, the lens of renaming doesn’t seem to extend to Edmonton’s city name itself – perhaps because the city’s namesake is relatively bland. But it’s an interesting exercise to ponder the implications of such a change, and consider how this would change the way you think of yourself as a resident here.

What does the name Edmonton mean to you, and what if that name changed? How do you feel when you imagine this place being called amiskwacîwâskahikan (or the more anglicized Amiskwaciy Waskahikan), or Omahkoyis, or Pehonan? How does your own identity change if “Edmontonian” no longer applies?

Photos by OpenStreetMap, City of Edmonton, Provincial Archives of Alberta.

Written by:

Tagged: