Digital dreams: Building an AI industry in Alberta

Business plan shows a promising future, but cash is needed to make it real

By Eliza Barlow

Edited by Therese Kehler

Disruption has been at the heart of the world’s three great industrial revolutions. Now it’s the buzzword for the proponents of artificial intelligence, the mavericks of supercomputing who are prepared to lead the world down a new path of growth and prosperity.

But what if the pathway is blocked, beset by detours and red tape?

That kind of disruption is a big worry among Edmonton’s AI champions. Last year they joined forces to form a steering committee, gave up their Friday afternoons for about six months and put together a business plan that they released in January.

The vision? A $235-million blueprint to turn Alberta AI into a billion-dollar economy by 2025 — including a $60-million ask of the provincial government to help them get there.

Dalibor Petrovic speaking at a community meeting on Sept. 24, 2018 to gather feedback on the AI business plan. (Photo: Mack Male)

‘PART OF ALBERTA’S FUTURE’

At the beginning of February, Dalibor Petrovic was on pins and needles. A partner at Deloitte who was part of the steering committee that developed the AI business plan, he didn’t want to imagine a scenario where a request for funding — presented to Alberta Innovates just weeks earlier — could be turned down.

“Not because of the money,” he said, “but because government investment is a signal on whether this is something that should be part of Alberta’s future.”

Petrovic’s worries were allayed on Feb. 13, when Premier Rachel Notley announced $100 million to attract more AI companies to the province.

The announcement, according to government officials, includes $58 million that is a new commitment for AI over five years. The remainder had already been allocated to two other agencies — Alberta Innovates and the Economic Development and Trade ministry — where it was earmarked for AI and machine learning initiatives.

With Alberta on the cusp of a provincial election, the announcement is one of a flurry of similar “investments” being announced by the NDP government. But regardless of which party forms the next government, Alberta’s long-term economic challenges will have to be addressed.

In the opinion of Alberta’s artificial intelligence advocates, a truly diversified economy — one that positions next generations for the jobs of the future — has to look beyond oil and gas. That means the need, and the ask, for AI support isn’t going away.

Nor will the tension between funding for research and commercialization.

Premier Rachel Notley announced in Calgary on Wednesday, February 13, 2019, that the Alberta government is investing $100 million to attract more artificial intelligence-based high-tech companies to invest in Alberta. (Photo: Premier of Alberta on Flickr)

WORLD-CLASS RESEARCH IS NOT ENOUGH

“If no one’s going to take up the mantle and do it, then goddamn it, I’m going to do it. It’s too important.”

These words come from Jonathan Schaeffer, artificial intelligence researcher and former dean of science at the University of Alberta. He stepped down from that position last fall, after a storied 35-year career in academia in which he authored hundreds of papers and created the first artificial intelligence program to “solve” checkers.

Schaeffer remains a professor in the Department of Computing Science but he has taken a one-year sabbatical from his university job. He is “being my own salesman for the city of Edmonton.”

His goal: “To help build this city into one of the great research and development and commercial centres for AI.”

Since beginning his effort, he’s spoken to more than 50 companies. Many are “looking at Edmonton,” said Schaeffer, another one of the 14 steering committee members for the January AI report, formally titled Realizing the Alberta AI Business Plan.

He says the reasons are clear — there are immigration problems and political uncertainty in the United States. Toronto and Montreal are vying for more AI businesses but there is a limited supply of expertise. Edmonton should be an obvious choice.

But what the AI ecosystem in Edmonton and Alberta has lacked — at least until recently — is major government investment and the expectation of private investment to follow.

“All things being equal, why would you come to Edmonton?” Schaeffer said in late January. “We don’t have the population, we don’t have the industrial base, we don’t have the geographical advantages.

“We have to work harder. Everybody, not just the government, has to contribute and help create something exceptional for Edmonton and Alberta.”

Jonathan Schaeffer. (Photo: University of Alberta)

Many Edmontonians only began to take notice of the city’s AI prowess in 2017 when Google DeepMind announced it would set up its first international research office here, with U of A professor Rich Sutton — considered a founder of reinforcement learning — at its helm. Around the same time, people started citing the statistic that the University of Alberta was ranked third in the world for AI research. (Rankings are based on information drawn from the website CSRankings.org.)

But the U of A has been a heavy AI hitter for a lot longer. It has been among the top three AI universities in Canada for 20 years, and in 2002, it founded the Alberta Ingenuity Centre for Machine Learning, since rebranded as the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute or Amii.

That institution has created more than 200 technologies including Chinook, Schaeffer’s world champion checkers program. Amii also offers programs that partner corporate and non-profit members with advisers to develop AI business strategies.

Edmonton’s research pedigree is laudable but it hasn’t led to commercial success, economic growth or even jobs. Most experts agree the vast majority of computing science graduates leave town.

Schaeffer says Edmonton’s AI research success is due to expertise that came about organically. Taking it to the next level will require a strategy.

“The province is in need of diversification. I believe we have an opportunity here, in some small way, to take a big step forward to diversify the economy,” he said.

“I’m not saying that AI is the answer. But it might be.”

RESEARCH OR RETAIL: A GOOSE-AND-EGG DILEMMA

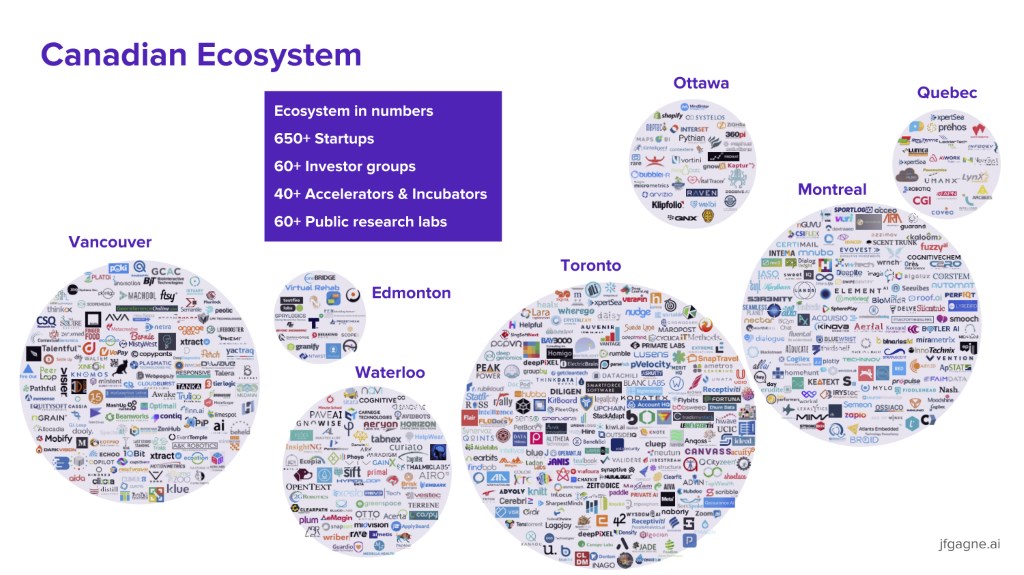

Jean-François Gagné, a successful Montreal AI entrepreneur, has created a diagram that depicts the size of the AI ecosystems in various Canadian cities.

With its colourful circles of different sizes, the diagram is reminiscent of the solar system. Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal look like Jupiter and Saturn. Edmonton? It looks about the size of Pluto, smaller even than centres like Ottawa and Waterloo.

It’s a stark representation of a very big challenge: balancing research and innovation against the pursuit of commercial endeavours.

Canadian AI Ecosystem 2018 (Image: Jean-François Gagné)

“I would be hard-pressed to give you an example of proven commercial success in AI in Edmonton,” said Ashif Mawji, head of the Edmonton branch of Rising Tide, a San Francisco venture capital company.

“Right now the issue is there isn’t any commercialization being done,” he said. “Wouldn’t it be great if we paired researchers with an accelerator, gave them pre-seed money, access to mentors, and let them scale up?”

As a member of the AI steering committee, Mawji advocated for a greater share of the government funding request to be earmarked for commercialization.

“Amii wanted a big chunk of the money, and I get it. I’m not faulting them for that. But the problem is our mindset — we’re very research-focused.”

The real hard work, Mawji believes, is commercialization. “That’s when you’re trying to sell it to somebody,” he said.

“In my viewpoint, if we fund commercialization what happens is (the resulting successful companies) are going to pump (their) own money into research.”

But John Shillington, CEO of Amii and steering committee advisor, offers a “more holistic view.”

During a Feb. 5 interview in his Amii office in downtown Edmonton, Shillington walked over to a whiteboard and drew a rudimentary crossing-the-chasm diagram, illustrating how research is the key first step that can eventually lead to a buzz of economic activity.

The academic work — research and innovation — is like the goose that lays the golden eggs. “You have to keep feeding it,” he said.

And there is some concern that, from a funding perspective, Edmonton’s research goose has not had as much fattening up as some others.

In 2017, Amii was one of three centres in Canada chosen by the federal government for investment in its Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy.

Of the $125 million pot, Amii got $25 million; the rest was divided between the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms (known as Mila and founded by professor and leading AI researcher Yoshua Bengio) and the Vector Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Toronto (lead by Geoffrey Hinton, a retired professor and Google vice-president who is viewed as a leading figure of deep learning.)

Shortly thereafter, Ontario and Quebec doubled down on the federal funding with investments of their own between $50 million and $80 million.

A week before the Alberta AI announcement, Shillington’s awareness of the funding discrepancy was evident. “When you look at where Mila is and where Vector is right now, there’s no question we’re lagging behind in terms of government support and industrial funding.”

South of the border, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is putting $1 billion into a new college of computing that is focused on AI and set to open in September.

The Alberta numbers are significantly smaller.

Since 2002, the Alberta government has invested about $44 million into Amii. Its researchers have leveraged this to obtain an additional $200 million in in-kind and grant funding.

Of the $58 million announced Feb. 13, Amii will receive $27 million, almost exactly what it requested to continue running its four programs at an accelerated speed. The government news release also said the money would enable Amii to expand with an office in Calgary. Steering committee members have told Taproot that Economic Development and Trade Minister Deron Bilous was keen that any strategy should be Alberta-wide.

Amii began hosting AI meetups last year to bring the artificial intelligence community together. The first was held on Sept. 10, 2018 at Startup Edmonton. (Photo: Mack Male)

“Amii is a huge asset that exists because Alberta Innovates invested in AI when AI wasn’t cool,” notes Cory Janssen, founder and CEO of AltaML, an Edmonton company that uses machine learning to create specialized business software.

Now, says Janssen, it’s time to capitalize on that investment. Researchers in Edmonton have done “amazing” work and their need for funding is important, he said, “but academic papers don’t pay mortgages.”

By the end of what Janssen describes as a “messy” process of democratic compromise, the steering committee for the AI business plan agreed on an almost 50/50 split between the research and commercialization sides of the government funding ask.

NERVOUS INVESTORS

How do we spur private capital into the marketplace? That is the question the AI business plan is trying to answer.

First, said Mawji, government should be providing financial assistance at the pre-seed level — in essence, the time when a company doesn’t even have a minimal viable product. This pre-seed funding allows fledgling companies to get a couple of years’ track record and reduces the investment risk.

Angel investors here, said Mawji, aren’t willing to get involved with companies that are just getting started. “In Alberta, the angels are seed or higher,” he said.

If, and when, companies manage to get off the ground, he said, “then venture capitalists take note.”

Janssen, who co-founded Edmonton company Investopedia.com in 1999 before selling it to Forbes Media in 2007, agrees there’s a “gap” at the pre-seed level in Alberta — and it’s a gap with a domino effect.

“There’s not going to be a lot of venture capital funding flowing into Alberta without the pre-seed funding,” said Janssen.

Investing in artificial intelligence doesn’t yet inspire the same confidence as investing in oil and gas or real estate. Janssen, along with other members of the steering committee, believes that’s partly to blame for the lack of private financial support.

“Part of the reason we don’t have a tech economy in Edmonton and Alberta is that things have been so good here for so long — the last few years notwithstanding,” said Janssen. “That’s what happens when you’re rich in resources. We haven’t had a reason to get into tech.”

Janssen hopes the business plan for artificial intelligence in Alberta will build those same “circles of trust,” but flowing into the tech industry instead of the oilpatch.

Access to capital for startups — literally, the cash to get things going — is another crucial part of the equation.

“Alberta is so far behind in terms of accessibility to capital,” said Janssen. “If you’re looking for seed capital, we’re nothing like Toronto and Montreal.”

Mawji’s idea is to invite bids from private accelerators to set up shop here. These would be firms like San Francisco-based Alchemist Accelerator, a venture-backed initiative that seeds about 40 tech enterprises annually, or Colorado-based Techstars, which opened its first Canadian accelerator in Toronto last year.

Toronto also has NextAI, an accelerator that, according to its website, gives its teams access to up to $200,000 in capital, world-renowned faculty and scientists, a network of Canada’s top business leaders and entrepreneurs, and access to cutting-edge AI tools.

“Part of the value the accelerator brings is private capital, access to venture capital,” said Janssen.

FROM RESEARCH INTO REALITY

Dornoosh Zonoobi, a research scientist with a PhD in medical machine learning, couldn’t agree more about the importance of capital to get Edmonton’s ecosystem going.

She’s a co-founder of Medo.ai, an Edmonton startup that’s working to commercialize AI for use in portable ultrasound devices. For its capital funding, Zonoobi and her colleagues found investors through a business incubator in Singapore, where she completed her graduate degrees.

Dornoosh Zonoobi, co-founder of Medo.ai (Photo: Mack Male)

“Access to funding over there is definitely easier. Those ecosystems are way more active. They do this every day,” she said. The Singapore government, she added, provides investor incentives like matching funds.

She met company co-founders — Jacob Jaremko and Jeevesh Kapur — while doing medical imaging research at the University of Alberta.

“If you don’t do any commercializing, your research would forever stay in research hospitals. It would not reach patients or anyone who actually makes a difference,” said Zonoobi.

Zonoobi and her team, comprised mainly of computing science graduate students from the University of Alberta, now work out of Startup Edmonton in the Mercer Warehouse. Their product is in the final stage of product development and clinical trials.

Zonoobi believes Edmonton has the potential to become an international hub for AI in health care. “People love Canadian companies. One important component of health-care products is trust. The moment you say you’re a Canadian company, that trust is already established.”

CAN WE KEEP THE TALENT?

Since mid-2017, when Medo.ai went to Singapore looking for investors, the Edmonton startup scene around AI businesses has grown, she said.

Others are noticing, too.

“The trajectory over the last year has been enormous. The number of companies that have set up shop here is incredible,” said Schaeffer.

“That’s exciting because those companies are bringing new jobs, high-paying jobs, skilled jobs to Edmonton, and what it’s doing is creating momentum and building critical mass in the ecosystem.”

Giving people a place to get their degree isn’t enough to get them to stay. For that, they also need to land a great first job.

“We’ve got this firehose of students who want to come to Edmonton,” said Schaeffer, who added that he’d like to see the U of A increase its capacity to admit those students.

Richard Sutton, Michael Bowling and Patrick Pilarski (Photo: John Ulan)

A big draw is Google DeepMind, lead by Rich Sutton, Mike Bowling and Patrick Pilarski, three of the University of Alberta’s leading AI researchers.

“Every student who graduates from the University of Alberta in AI wants to work for Google DeepMind. They get the best of the talent,” Schaeffer said.

What Edmonton’s tech economy needs are more places like that, job offers that the brilliant minds graduating from the university’s computing science department simply can’t pass up.

“They’ve been through a winter, they understand what it’s like — they will stay here if there are jobs,” Janssen said. “But when we don’t have that initial first job, you lose them.”

THE POLITICS OF FUNDING

The Feb. 13 announcement by Notley, signalling an intention by the provincial government to work toward building an industry of artificial intelligence in Alberta, was roundly perceived as a step in the right direction by members of the AI steering committee.

Now, most are waiting to hear more details on the funding package and what other elements of their plan might be funded. A government spokesman says more information on program roll-outs will be released in the coming weeks.

Janssen noted the message of government support is important for people outside of Alberta to hear.

“Even the perception that something’s happening here makes a big difference,” he said.

But the looming election — it must be held before May 31, 2019 — can’t be ignored. The AI announcement was one of many promising millions in investment across multiple sectors; the amount seems tiny compared to the following week’s promise of a $3.7 billion “investment” in increased rail capacity to move Alberta oil to market. Should the government change, many of these commitments could be reviewed.

It’s clear that Edmonton’s champions of artificial intelligence don’t agree on which of its players are most in need of funding. But they all agree that government funding is critical to getting the business of AI out of the lab and into the market.

They also agree that the time is now. And that this opportunity to build Edmonton’s AI industry won’t stick around forever.

“I’ll be happy when we have a company that raises tens of millions of dollars and hires hundreds of people,” Janssen said. “I’ll be happy when the next unicorn (a tech startup valued at more than $1 billion) comes from this province.

“I’ll be happy when everybody’s talking about how Alberta’s now the place you want to be when starting a company with machine learning, despite the weather.”

Header photo by geralt on Pixabay. Feature photo by Jonathan Crews in Sylvan Lake, Alberta on Unsplash.

Written by:

Edited by:

Tagged: